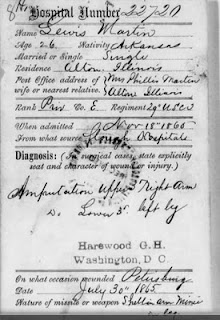

Face of Pvt. Lewis Martin of 29th US Colored Infantry

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

His face is one of the most famous in Civil War history. He was one of the countless men who were injured in the Civil War, and as famous as his face is, we don't know his story.

When I examined his story I was surprised to learn that he was born in Arkansas.

From Service Record of Lewis Martin

Not only was he born in Arkansas, but he had apparently been freed prior to the establishment of the US Colored Troops. In fact he was a free man prior to the beginning of the Civil War, as his record clearly states that he was free before April 1861. In February of 1864, he enlisted in the Union Army and was placed in Company E of the 29th US Colored Infantry.

I can see that he was a tall man---over 6 feet in height, and was in the prime of his life as a 29 year old man.

His unit was organized in Quincy Illinois, and he joined the regiment in Alton Illinois. Not long after the unit organized, they were dispatched to Annapolis Maryland, and then quickly from there they went into Virginia, directly into the heart of the Civil War.

As I imagine this man, born a slave in Arkansas, who somehow became free, was living in Illinois---this is a man who could have avoided the battle completely. He was freed before the war had started, and there was not much enthusiasm for black soldiers to enlist until 1863. He could have continued his life as a free man, living in the free north, but---the joined the battle to free his brothers, and enlisted.

He would be wounded while in Virginia, and his record noted that he was wounded at the battle of Petersburg.

Lewis Martin was confined for some to a hospital in Alexandria Virginia. Records from January through June of 1865, he was still suffering form his wounds, and still a resident of the hospital. There are not many images of the military hospital in northern Virginia, but he may have been near this one facility that was known as a Convalescent Camp.

Convalescent Camp near Arlington Virginia

Image from National Archives. Mathew Brady Collection

Later in 1865, Martin was moved to Harewood Hospital. While there, his wounds having continued to plague him a description of his injuries and treatment were described. His arm was amputated above the elbow and his left leg was amputated below the knee.

Record showing amputations that Pvt. Martin had to undergo

Considering the nature of his wounds, clearly moving the soldier even a short distance from a hospital in Northern Virginia, would have a been a painful one, in one of the military ambulance wagons that were used during this time. He might have been moved in one of the Harewood Hospital ambulance trains such as the one below.

The Ambulance Train of Harewood Hospital in the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Division, Washington, D.C.;

The ambulance train would have taken him to the facility shown below.

Harewood Hospital in Washington DC. The capitol dome can be seen in the distance.

Source: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War

Eventually Pvt. Lewis was mustered out when his unit was, but he was not with them. They were in Brownsville Texas when disbanded, but he would suffer from his wounds for the remainder of his life.

I have many more questions about Pvt. Lewis the man. I plan to continue to study his life to learn a few details more.

How did he become free?

When did he arrive in Illinois?

There was a population of free people in Alton Illinois where he lived when he enlisted. Was he involved in the activities of the Underground Railroad In Alton Illinois at the time he enlisted?

Did he return to Illinois after the war, or remain in Washington?

Did any family remain with him during his final years?

I do know that Pvt. Martin was eligible for a Civil War pension. He applied for one and received it.

Civil War Pension Index Card

Private Lewis Martin

There is more to the story of Private Lewis Martin.

He was a single man when he enlisted so there was no widow to later collect a pension after his death. He had a relative who was quite possibly his mother, and she lived in Alton Illinois, the city where he enlisted. Her name was Mrs. Phillis Martin.

Close up image of hospital record of Pvt. Lewis Martin

Did Mrs. Martin learn of her son's injuries, and did she join him after the war in Washington? Did he return to Illinois after the war? Did they ever see each other again?

When did he die, and where could he be buried? I plan to conduct some research on Private Martin to find the answers to these questions from his Civil War Pension file.

I mentioned that his face is one of them most famous.

I showed only his face above, but I am compelled to share the un-cropped photo below as it appeared on his Disability Certificate.

Disability Certificate from Civil War Service Record of Pvt. Lewis Martin, Co. E 29th US Col. Infantry

Rest well, Private Lewis. May your service always be remembered.